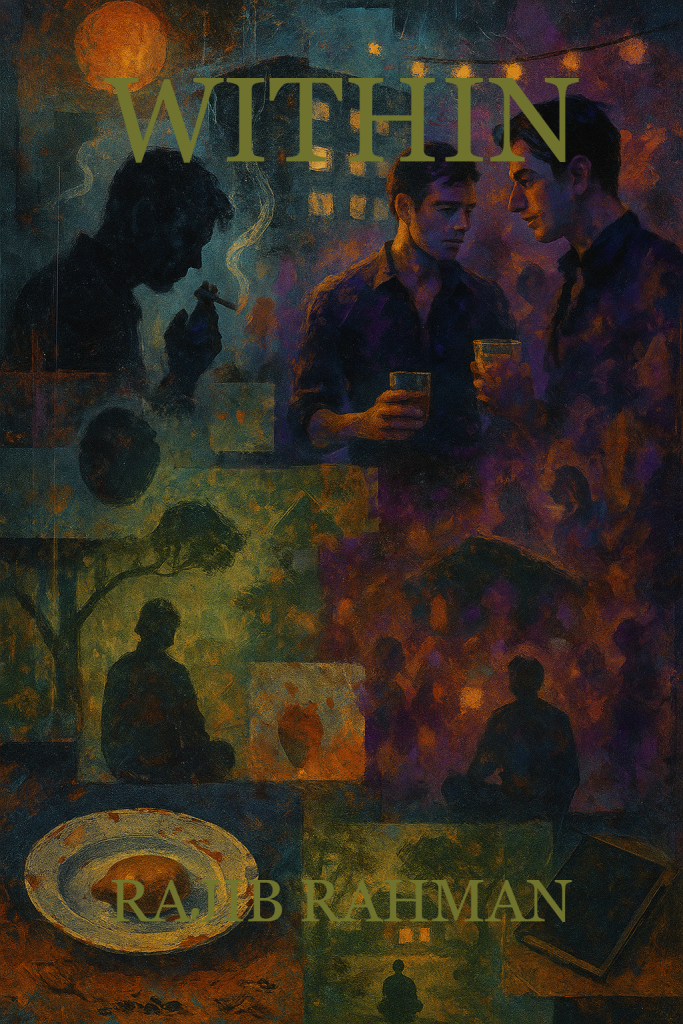

within

A Sequel to “Elsewhere” and “Stillness”

Part I

The night Miran got married, Rayhan couldn’t sit still.

It began not as panic or heartbreak, but a low, indistinct hum in his chest, like the faint vibration of an elevator cable somewhere deep below ground. He first noticed it while brushing crumbs from his breakfast plate into the sink, his thumb catching against a jagged crack in the ceramic. The plate had been chipped for weeks, but that night, it felt like a quiet metaphor.

The apartment was too still. The air too still. Even the ceiling fan, a constant in his studio on the third floor of a building that always smelled vaguely of fresh plants and washed clothes, seemed to creak more hesitantly than usual.

The city outside moved with the distracted rhythm of early evening. A bicycle bell chimed from the lane below. A child cried in protest, no clear reason, just the shrill exhaustion of being denied something small. The neighbors on the second floor had begun their evening prayers. Familiar sounds. But tonight they felt misplaced, as if Rayhan had entered the scene halfway through and forgotten his lines.

He stood barefoot in his kitchenette, rinsing the last traces of tea leaves from his cup. His eyes fell to the compost bowl by the counter, a mango pit placed neatly inside, its fibers stripped with precision. It had been from yesterday’s breakfast. Something about its quiet finality made him wince. Then came the memory, Miran laughing months ago, spitting mango threads into a tissue, calling him a pretentious bastard for slicing the fruit instead of biting in.

He reached for his keys. Left the lights on. Didn’t take his wallet.

He walked aimlessly. A journalist by profession, Rayhan had long trained his eye to pick up what others missed: a graffiti tag fading on a tin wall, a rickshaw painted with the face of a long-forgotten actor, the way one traffic cop always tapped his baton three times before signaling. But that night, nothing stuck. His gaze slid off the city like rain on glass.

He passed roadside tea stalls, the scent of over-boiled cha rising from glasses fogged with sugar steam. A man in a lungi swept dust into a pile the wind kept undoing. He passed a bakery he once wrote about in a lighthearted Sunday column, “Places Dhaka Forgot to Gentrify.”

He used to love writing those.

By the time he reached Gulshan, his legs were sore. He hadn’t planned to come here, but the streets had curved toward it. He stopped opposite Miran’s building, beneath a flickering orange light that seemed too loud in its inconsistency.

Seven floors up. A soft-lit living room. Neutral drapes. Probably a bowl of sugared almonds on a side table. Guests filtering out by now. Saira, in off-white. Miran, maybe barefoot by now, collar loosened. Married.

Rayhan lit a cigarette with fingers he couldn’t keep from trembling.

“All is well,” he said aloud, quietly. Not to the building. Not to the evening. But to himself.

Once. Then again. Then again.

The smoke rose upward, indifferent.

He returned to his flat and sat on the edge of his bed for what felt like hours. The room smelled faintly of old paper and forgotten life. He didn’t cry. Not because he didn’t want to, but because some part of him had unlearned it. It was as if grief had settled somewhere too deep to reach.

In the morning, he made tea he didn’t drink.

At work, no one noticed. He edited a piece about plastic pollution in the Buriganga with ruthless precision, then made a joke in the newsroom about how the Minister for Water Resources had the diction of a haunted typewriter. His colleagues laughed. He smiled easily. A junior reporter asked him for advice on a lede, and he offered three variations, all good, all confident.

By lunch, he had forgotten which of the headlines he’d written himself and which he’d only polished.

Rayhan’s life, up until recently, had been marked by a certain affable distance; the kind that kept him liked, but safely unknown. He was affectionately teased for his print-era romanticism. He often carried a black notebook, claiming phones were too loud for thoughts worth keeping. At office dinners, he made fun of menu typos and was always the last to leave.

He had friends. Real ones. A tight trio from college, an editor who still called him “kid,” a dear friend in Savar who sent him memes with zero context. Most days, he replied to them all. But lately, texts sat unread longer and longer. Not out of malice, just delay. And the longer he delayed, the harder it became to begin again.

He declined three dinner invites in a row. Claimed deadlines, stomach bugs, a visit to his parents once. He couldn’t tell if the excuses were transparent or if his friends simply chose to look away.

He wasn’t waiting. Or at least, that’s what he told himself. Each time his phone vibrated, he looked without hoping. He wanted to believe he had made peace with it. But absence had its own gravity. It rearranged things quietly.

Two days after the wedding, Miran called.

“Hey.”

Rayhan froze mid-step in the grocery aisle, holding a tin of coconut milk he had no intention of buying.

“I just wanted to say,” Miran’s voice was soft. Measured. “It’s just a piece of paper. Nothing’s really changed.”

Rayhan closed his eyes. The sound of Miran’s voice, filtered through the static of grocery music, felt like warm water on a bruise.

“I know,” he said.

He meant it. Or wanted to. But in some wordless part of him, he felt the ground shift.

They started meeting again. Casually. Public spaces only. Cafés where the music was soft and the chairs were uncomfortable. Bookshops. The shaded edge of Gulshan Lake.

The ease remained, but it had thinned. There was a new caution in Miran, like someone balancing a glass bowl on a tightrope. They talked of business, politics, how absurd the city’s billboard regulations were.

“How’s work?”

“Busy,” Miran said.

“Mine too,” Rayhan replied, though it wasn’t true.

He’d started missing deadlines. Not dramatically, just subtly. He opened documents and stared at blinking cursors. His thoughts, once sharp and nimble, now wandered like unsupervised children.

One evening, after editing a piece about rising urban loneliness among youth, he sat alone in a café in Gulshan 1, MacBook Pages open but blank. Outside, a man sold balloons with LED lights inside. Children tugged their parents toward the shimmer. Rayhan watched them, feeling as though he were behind a pane of thick, soundproof glass.

Later, in the same café, a colleague from Features waved at him.

“Rayhan bhai! Alone?”

He nodded. “Waiting for inspiration.”

She laughed, sat briefly, then frowned. “You’ve lost weight. Everything okay?”

“Just stress,” he said. The words came easy now. A shorthand for everything unsayable.

That night, at home, he stood by his bookshelf, fingertips grazing titles. The spines felt unfamiliar. He pulled out Giovanni’s Room, opened to a page at random. A line stared back: People who believe that they are strong willed and the masters of their destiny can only continue to believe this by becoming specialists in self-deception. He closed the book.

A neighbor’s pressure cooker hissed. The building shifted on its foundations like an old man adjusting his knees.

Rayhan sat at his desk, opened a blank Word document, and typed one line: What do we call it when something ends before it begins?

He deleted it. Then switched off the lamp.

Some nights, he walked aimlessly. Through Bailey Road, where the scent of cha and burned sugar lingered; through Banani, where his uncle used to live before they sold the flat. Once, he passed the lane near his childhood home and paused by the banyan tree that used to drop seeds onto their windowsill.

Everything looked smaller now. The gate, the sidewalk, even the tree.

At work, he wrote less. His pieces, once sly and lyrical, had become sparse. One editor asked if he was tired. He smiled and said, “Just mellowing.”

At home, he watered his money plant without checking if the soil was already damp. It kept growing anyway.

One morning, while brushing his teeth, he caught his reflection and stared longer than usual. The face looking back wasn’t sad. It was just… unfinished.

He dreamed of Miran sometimes. Not dramatic dreams. Not even romantic ones. Just odd fragments; standing next to each other at a traffic signal. Laughing in a concert. Miran pointing out a cracked ceiling.

Waking up from those dreams hurt more than he admitted. He didn’t tell anyone. Because what could he say? He hadn’t been betrayed. There had been no fight. No promise broken. Just a quiet, slow rearrangement of lives.

And yet, something in him had been misplaced.

One evening, as the sun dipped behind the mosque minaret and the sky turned the color of rusted iron, Rayhan stood by the window with a cup of tea gone cold. He thought: I used to be good at being alone. The thought felt foreign now.

He closed the window. A breeze moved through the screen, soft, faint, enough to carry the distant sound of traffic fading into itself. He let it pass through him.

And for a moment, he did not resist.

Part II

The after-party unfolded on the rooftop of a private venue in Gulshan 2, one of those places that looked like it had been designed not only to host people, but also to frame them. Black was the dress code. Everyone obliged. From short modern black dresses to velvet blazers with exaggerated lapels, the city’s well-dressed, well-fed, well-followed showed up on time and camera-ready. Strings of dim LED bulbs flickered overhead, too curated to be mistaken for stars. The air was thick with bass and perfume, stitched together by the dry bite of rooftop wind and something sharper; molly, maybe; or just the edge of anticipation.

The DJ played what everyone expected, global beats, a familiar pulse. Lagos house followed by Berlin techno, a viral remix of a track people half-knew but danced to like it was an anthem. Laughter punctuated the night like applause. People kissed, disappeared into corners, spilled drinks and apologies with equal elegance. The rooftop smelled like sweat and sweetness and whatever it was that made you believe, just for a few hours, that nothing outside these walls could touch you.

Rayhan had arrived early, out of loyalty, maybe. Or habit. Or the desire to lose himself among people who didn’t know the precise shape of his sadness. He stood still for a while, drink in hand, a smoky mezcal concoction with a chili rim and a candied citrus twist. It looked like a photograph someone else would post. It tasted like a dare he hadn’t meant to take.

He watched people laugh too loudly, hug too long: or too short. There were girls in feathered sleeves and boys who talked with their hands. Someone handed him a second drink. Another passed him a tab- acid, probably; pressed into his palm like a secret. He swallowed it without asking.

He didn’t feel the moment Miran arrived. He only noticed the shift. Like static before a song. Like gravity remembering its job.

It was past midnight. Miran stepped onto the rooftop dressed in sharp black, a pressed shirt, sleeves rolled just high enough to show a faint vein on his forearm. His hair was still damp, maybe from a rushed shower or maybe just the effort of appearing unbothered. He moved through the crowd with that practiced elegance Rayhan had always noticed, like someone walking through a dream they knew they wouldn’t remember.

Rayhan sipped his drink too fast. His fingers drummed the glass as he debated walking over, then didn’t. The old rhythm of waiting, of watching Miran in motion, returned like a twitch.

They didn’t speak at first. Didn’t need to. Rayhan watched him from a distance, noting how Miran tilted his head when pretending to listen, how he cradled his drink like it contained something heavier than alcohol. The city slept below them. Miran stood near the bar, laughing. Rayhan hated how easily he could still recognize that laugh from across a room; how it knifed cleanly through music.

Eventually, they drifted into the same orbit.

“You came,” Rayhan said, when they found themselves shoulder to shoulder by the drinks table.

Miran turned, faint smirk in place. “You sound surprised.”

Rayhan shrugged. “Not really. Just didn’t think it’d be tonight.”

Miran lifted his glass and examined it. “They’re putting saffron in mezcal now.”

“It’s a time to be alive.”

Miran’s smile didn’t quite reach his eyes. Neither of them reached for more words.

Later, someone passed them another round of drinks, taller this time, brighter, tasting of guava and heat. Someone else passed a tab with a quiet nod. Miran hesitated, then tipped his head back. Rayhan followed. The music thickened. The rooftop tilted slightly, then steadied.

For a while, everything felt less sharp. The sky bled purple above them. Conversations turned glossy. A girl laughed beside them and Rayhan felt the sound ripple through his ribs. Miran leaned in to say something about the groom’s ridiculous shoes but forgot the punchline halfway through. They both laughed anyway. Giddy, careless, young again for just a minute.

They danced.

Not with abandon, exactly, but with the looseness of people no longer pretending not to feel. Rayhan moved like he used to, before nights like this started to feel like acting. Miran was beside him, shirt half-untucked, sweat beading at the back of his neck, eyes closed too long for just the music. The lights cast them in flashes; gold, then blue, then the soft flicker of something almost real.

It wasn’t joy, not quite. But it passed for it.

For a brief, weightless hour, they existed in a version of the world where nothing had yet been broken. Where everything, somehow, still had time to begin again.

Around 3 a.m., they left together, not planned but not accidental either. They didn’t speak as they stepped into the rickshaw. The city had emptied. The roads glistened with the day’s dust settled by humidity.

They rode in silence, the kind that didn’t ask for breaking.

Miran leaned into him slightly. Not obviously. Just enough.

Rayhan felt the warmth of his shoulder before anything else. Then the weight. Then the memory of every time he’d told himself this would never happen.

“Can I kiss you?” Rayhan asked.

He hadn’t meant to say it aloud. The question had floated to his lips and slipped out before his self-control could retrieve it.

Miran didn’t hesitate. “Yes, Rayhan.”

It wasn’t a movie kiss. It was slow, uncertain, both of them too aware of the world still turning around them. The air tasted of diesel and something sugary from where they had no idea. Rayhan’s fingers curled slightly against the edge of the seat, his other hand suspended awkwardly midair. He kissed him the way one presses an old photograph to their chest; gently, fully aware of its fragility.

Miran didn’t pull away.

Rayhan felt his breath rise and fall. For a few seconds, nothing else existed.

Then it ended. Not abruptly, but with the sense of a curtain falling mid-scene. The rickshaw turned a corner. They didn’t speak.

When they reached Miran’s place, he stepped down, lingered for a second, then said, “Bye, Rayhan.”

Rayhan nodded, not trusting himself to respond. He rode home alone. The streets blurred past, all neon signs and stray dogs. He touched his lips once. Just once. Then stopped himself.

Two weeks passed.

The city moved on. Load-shedding returned. The humidity rose. Rayhan’s neighbors started keeping their windows open, and the sounds of strained marriages filled the building like water.

He met Miran again, this time for iftar. A quiet table at a café in Gulshan 1, too dimly lit for small talk.

They ordered a traditional iftar platter- dates, haleem, jilapi, and soft flatbread still warm to the touch.

Miran looked tired. Not in the way people do after work, but in the way people do after trying too hard to be happy.

Halfway through the meal, he said, “You shouldn’t have kissed me. I was drunk.”

Rayhan looked up, blinking slowly, trying to make sense of what he was hearing.

“I was drunk too,” he replied. “But I remember asking. And you said yes.”

“That doesn’t mean you should have.”

Rayhan didn’t speak. Not immediately.

Miran went on. “You’re older than me. I thought maybe you’d know better.” He paused, then looked away. “I don’t know.”

The words didn’t sting so much as echo. Rayhan nodded. Once. Then returned to his haleem, now lukewarm.

Across the table, Miran stared into his tea. Whatever else he wanted to say remained there, unsaid.

He returned to the newsroom, to the rhythm of edits and deadline caffeine. But the spark that once animated his voice- the dry wit, the shoulder nudges, the minor rebellions- had faded. His colleagues noticed. The younger ones kept a careful distance. His editor once asked, “Still working on that feature about loneliness in the city?”

“I might scrap it,” he said.

“You shouldn’t. It’s good. Honest.”

Rayhan nodded, noncommittally. He was tired of honesty. It never gave anything back.

He stopped replying to friends. Missed two birthdays. Skipped his cousin’s get-together at Cantonment. The weight came off slowly, almost politely. A little less rice at lunch. Coffee instead of breakfast. His belt notched tighter. His shirts fit differently.

At one point, he saw himself in the mirror; collarbones sharp, eyes too large for his face, and thought: I look like someone playing grief.

His neighbor, Mrs. Aziz, once knocked on his door to return a book he’d lent her months ago. She paused when he opened the door.

“Baba, you look pale. Are you ill?”

“No,” he said. “Just quiet.”

She didn’t ask again. Only handed him back the book, Interpreter of Maladies, and said, “That one made me cry.”

He wanted to reply, Me too, but didn’t.

Saira called one evening without warning. Rayhan was folding laundry, half-listening to an old podcast rerun about shipwrecks.

“Hey,” she began, breezy, practiced. “Do you still have that book, The Crash, by Freida McFadden? I think you once mentioned it.”

Rayhan paused. “No,” he said. “Never read it.”

A beat.

“Oh,” she said. “Thought maybe Miran borrowed it from you.”

There it was.

He moved to the window, watching the heavy sky tremble above the power lines. “Haven’t spoken to him in a while,” he said.

Saira made a sound, somewhere between a hum and a sigh. “He’s been quiet. Lately. Like really quiet.”

Rayhan said nothing.

“I mean, he talks,” she added quickly. “But it’s like he’s not sending the words to the same address anymore.”

He did. But he didn’t say that.

“He sleeps late,” she continued. “Forgets things. Once he didn’t touch his food for hours. Just stared at it.” Her voice cracked there, so slightly he wouldn’t have noticed if he weren’t already attuned to the tremble people try to hide.

Rayhan looked at the books on his shelf. None of them had answers. “Maybe he’s just tired.”

“Maybe,” she said. Then, in a lower register: “Sometimes I feel like there’s this whole section of him, cordoned off. Like I have the map, but he moved the borders.”

Rayhan didn’t respond. Not out of cruelty. Just, he didn’t know where to place his voice anymore in this triangle that had collapsed in on itself.

“You and I,” she continued, “we never really talked, huh?”

“No,” Rayhan said. “We didn’t.”

Another pause.

“I’m not trying to pry,” she said, which, of course, meant that she was. “I just want to know what I’m dealing with.”

He almost smiled at that. “He’s not a project,” he said, gently. “He’s a person who keeps pieces of himself in locked rooms.”

“I don’t want to fix him,” she said. “I just want all of him.”

Rayhan’s breath caught, then evened. “That might be the same thing.”

Neither of them spoke after that. The silence was not awkward. Just final.

“Okay,” she said, eventually. “Sorry for bothering you.”

“You’re not.”

“Goodnight.”

“Night.”

She hung up before he could say anything more.

Part III

He arrived at the Vipassana center with a duffel bag, a notebook he wasn’t allowed to use, and a body that felt older than it was. Dhamma Ganga lay on the outskirts of Kolkata, nestled behind a stretch of farmland, past low-lying homes with cracked paint and sleepy verandas. The air smelled of wet earth, incense, and wood smoke. It was quiet, disconcertingly so. Even the birds seemed measured.

The compound surprised him. It wasn’t austere, not in the way he’d imagined. It was quiet, yes, but quietly alive. Giant mango trees formed a shaded corridor between the dormitories and the meditation hall. There were guava trees and Indian berry shrubs, the smell of ripe fruit occasionally sweetening the wind. Birds flitted without urgency, as if they too were under instruction not to disturb.

The center was divided neatly into four structures: a large men’s dormitory on the first floor; six smaller single rooms in a line beside the garden, beneath which sat the men’s dining hall and kitchen. A low concrete wall separated the men’s side from the women’s. Their accommodation mirrored the men’s, with their own kitchen and garden path. The only space shared by all was the meditation hall, a square, high-ceilinged room lined with cushions, fans turning quietly above. There were around eighty students- forty men, forty women. By day six, a third of them had left. Their absence echoed more loudly than their silence ever had.

On the first evening, they gathered for orientation. Rayhan sat cross-legged on a cushion in the meditation hall, eyes darting between strangers who would soon become reflections of himself- tired, hopeful, wrecked in ways they didn’t speak of. The instructor, a man with a calm voice and no unnecessary syllables, explained the schedule: wake at 4 a.m., meditate until 9 p.m., short breaks for food and rest. No phones. No talking. No running away.

Day one was manageable. The novelty cushioned the discomfort. The silence felt like a game. He watched ants carry away crumbs after breakfast. Counted his steps from dorm to hall. Noted the way the light moved across the floor.

Day two clawed deeper. The quiet became dense. Time stretched. His knees ached. His spine barked. Memories surfaced like driftwood in floodwater, blunt, unsummoned. The steam rising from his meal curved briefly, absurdly, into something like Miran’s profile. He heard his sister yelling down the hallway of their childhood home. Felt his father’s hand, rough and brief, on his shoulder after he failed his first math exam.

By day three, his body mutinied. Fever rippled through him like a whispered threat. Every limb throbbed. Aches lodged in his jaw, his hips, his ankles. He stood by the bathroom mirror and didn’t recognize himself- eyes sunken, lips chapped, a thin crust of dried sweat lining his collarbone. For a moment, he imagined boarding a plane back to Dhaka, the relief of failure wrapped in justification.

He almost left.

But he didn’t.

He sat through the next day’s sessions, teeth gritted, breath shallow. The technique was deceptively simple: observe the breath, observe the body, resist the urge to react. But in practice, it felt like drowning in slow motion. Waves of sensation moved through his body- itching, burning, pressure- demanding a response he refused to give. It was not endurance; it was surrender, of the difficult kind.

And then, quietly, something gave way. On day five, his breath shifted. He noticed it; cool at the tip of the nose, warm at the upper lip. He watched it like a stranger, like a guest he wasn’t sure would stay. The world outside shrank. Inside, there was space.

By day six, he could hear things more clearly: the wind rustling the mango leaves, the scrape of ladles against steel in the dining room, the precise clink of another student adjusting their posture. These sounds became his world. The hunger for distraction fell away, revealing the raw mechanics of being alive.

He began to see his mind as a cluttered attic. With each sit, he swept a corner. Behind the dust, he found forgotten things- small, soft memories. Miran’s head tilted back in laughter. His mother’s hand on his fevered forehead. A moment, long ago, watching monsoon rain with no need to move.

And dreams came, not nightly, but when they did, they arrived with clarity. In one, he wandered through a train station calling Miran’s name, never finding him. In another, he walked through rooms filled with mirrors but couldn’t see his own reflection. He woke from these dreams not with panic, but with recognition, as if grief, too, could evolve.

He didn’t speak, but language returned in new forms; through sensation, image, breath. What remained was a structure he hadn’t seen in years, a mind not consumed but composed.

The grief, when it came, was clean, arriving like a breeze through an open door. No longer barbed. He saw how much he had mistaken being needed for being loved. How his longing had masked itself as devotion. How silence didn’t empty him but revealed what had always been crowded inside.

He forgave Miran. Not because he stopped loving him. But because he understood that Miran didn’t owe him anything beyond what he could give.

He forgave his sister, too. And his father. Their cruelties had their own bruised origins. He didn’t excuse them. He simply let them drift downstream.

The days blended. The silence remained steady. And then, on the ninth day, he forgave himself.

Not in grand gestures, not with epiphanies. But with the slow acceptance that some wounds do not disappear; they simply stop dictating the terms of your life.

When he returned to Dhaka, the air felt thicker, familiar. The city roared like always: horns, hawkers, the lurch of buses. But he walked through it differently. Like someone not pressing forward, just moving.

In his apartment, he opened the windows. Watered his plants. Made tea.

His fingers hovered over the power button. For a second, the idea of letting the silence stretch another day tempted him. Only then did he turn on his phone. It buzzed like a trapped insect. Messages poured in, some from colleagues, one from his editor, a voice note from a college friend. And a message from Miran.

He read them all. Replied, where needed. Brief, warm. Then he archived Miran’s thread.

He didn’t delete it.

But he didn’t open it.

Not out of anger. Not to sever. Just because he no longer needed to.

That evening, he took his tea to the balcony. The air smelled of rain and concrete and something green, like bruised guava leaves or the stem of an unripe mango. A money plant, neglected for weeks, had curled toward the light and touched the grill.

Far off, a pigeon returned to its usual perch, cooing once before settling. The ordinary sound, tonight, felt like a beginning.

Rayhan watched it. Not for a reason. Not out of habit. Just watched.

The sky, behind the haze, began to darken with purpose. Not dramatic. Not cinematic. Just evening arriving the way it always did- slow, certain. The city breathed below.

And for the first time in months, so did he.

~ September 2025

Disclaimer: This tale was crafted from imagination. If it mirrors your own story, well… maybe we share the same dreams.